Rodrguez’s acquaintance was one of the 12,000 people who perish each year from Chagas, a distinct kind of monster known as a “silent and silenced disease” spread by nocturnal insects and affecting up to 8 million people annually.

Emiliana Rodrguez, 42, still has Chagas disease, which she describes to as a “monster,” despite moving from Bolivia to Barcelona 27 years ago.

“The terror frequently struck at night. I occasionally didn’t sleep,” she admitted. “I was worried that I would fall asleep and not awaken.”

Eight years ago, when Rodriguez was expecting her first child, she discovered she was a Chagas disease carrier.

In recalling the passing of her friend, she continued, “I was paralyzed with shock and remembered all the stories my ancestors told me about people suddenly dying. I thought, “What’s going to happen to my baby?”

Rodriguez, however, underwent medication to prevent the parasite from infecting her pregnant child via the placenta. The test result for her infant daughter was negative.

Before her daughter was diagnosed with the silent killer, Elvira Idalia Hernández Cuevas, a mother of an 18-year-old in Mexico, had never heard of Chagas.

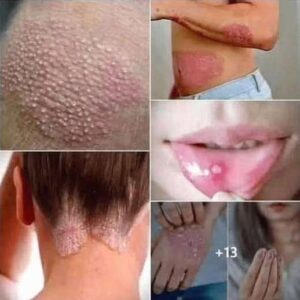

Teenager Idalia from Mexico contracted Chagas disease while donating blood in her community close to Veracruz. Chagas is a disease spread by triatomine bugs, sometimes known as kissing or vampire bugs, which feed on human blood.

According to Hernández in an interview with the Guardian, “I had never heard of Chagas, so I started to research it on the internet.” “When I read that it was a silent murderer, I was horrified. I was clueless as to what to do or where to go.

She is not alone in this; many people are unaware that these bothersome insects might spread disease.

The initial human case of Chagas disease was found in 1909 by the Brazilian physician and investigator Carlos Ribeiro Justiniano Chagas.

The Americas, Europe, Asia, and Oceania are now part of the Chagas disease’s geographic range, which has grown in recent decades.

In low-income homes in rural or suburban areas, kissing bugs come out of hiding when people are asleep at night.

When an infected bug bites a person or animal and then urinates on the skin, the probability that the victim will scratch the area increases, increasing the chance that the feces may enter the body through skin cuts or open sores.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 6 to 7 million people worldwide have Chagas disease, most of whom are unaware of their illness.

These people are based in South America, Central America, and Mexico.

For a lifetime, the lethal infection may go untreated. In Latin America, Chagas kills “more people than any other parasite disease, including malaria,” according to the Guardian, killing over 12,000 people annually.

Even though these bugs have infected nearly 300,000 people in the United States, the issue is not widespread.

According to the CDC, even among those who never show symptoms, 20–30% can endure gastrointestinal problems that can be extremely uncomfortable decades after the initial infection or heart problems that could be fatal.

A worldwide diagnosis rate of just 10% makes treatment and prevention more challenging.

Hernández and her daughter Idalia visited several doctors in pursuit of assistance, but they knew nothing about Chagas disease or how to cure it.

“I was shocked, terrified, and heartbroken because I believed my kid would pass away. I was particularly anxious since I couldn’t find any trustworthy information, Hernández said.

When Idalia contacted a relative who works in medicine, she got the help she needed.

“In Mexico, the authorities claim that there aren’t many people affected by Chagas and that it’s under control, but that’s not the situation,” says Hernández. “Medical workers lack training and confuse Chagas with other cardiac conditions. Most people are unaware that Chagas exists in Mexico.

The World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes Chagas disease as a neglected tropical disease in terms of global health policy.

Treatment for Chagas illness

Chagas is ignored, in part, because “it’s a silent disease that stays hidden for so long in your body… because of the asymptomatic nature of the initial part of the infection,” according to Colin Forsyth, a research manager at the Drugs for ignored Diseases Initiative (DNDi).

Forsyth added, “The affected just don’t have the power to influence healthcare policy.” to his earlier remark. It’s kept secret because to a convergence of biological and social problems.

As the illness spreads to other continents, it has recently come to light that Chagas disease can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy or childbirth and through blood transfusions and organ transplants.

The Chagas Hub was established by Professor David Moore, a physician at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in London, with the goal of “more people being tested and treated, and to manage the risk of transmission, which in the UK is from mother to child,” he added.

In response to the WHO goal of eradicating the illness by 2030, Moore said, “I can’t conceive that we’ll be anywhere close by 2030. Progress toward eradicating Chagas is “glacial.” That is incredibly unlikely.

According to Moore, the 50-year-old or older treatments for Chagas disease are “toxic, unpleasant, and not particularly effective.” Nifurtimox and benznidazole are two of these medicines.

The same medications may be able to stop or slow the condition in an adult, but this is not guaranteed in the case of newborns.

The worst symptoms Rodriguez experienced were an allergic rash, lightheadedness, and nausea. Now that her therapy is through, she only needs yearly checkups.

Moore contends that more effective treatment is necessary to stop the spread of Chagas disease, but pharmaceutical companies do not currently perceive a profit in creating such medications.

Hernández’s goal as president of the International Federation of Associations of People Affected by Chagas Sickness (FINDECHAGAS) is to raise awareness of the disease so that more cures can be developed.

What should I do if I think I’ve uncovered a triatomine bug?

To stop this “monster,” Rodriguez is currently in Spain, collaborating with the Barcelona Institute for Global Health to increase public understanding of Chagas disease.

The silence is getting to me, says Rodriguez. “I want people to discuss and be aware of Chagas. I want everyone to receive testing and care.

Furthermore, people are listening to them.

The World Health Organization designated April 14 as World Chagas Disease Day in recognition of the day in 1909 when Carlos discovered the first human instance of the disease.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “Global targets for 2030 and milestones are set to prevent, control, eliminate and eradicate a diverse set of 20 diseases and disease groups.” Chagas is also covered.

The following steps are suggested by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to prevent an infestation:

The areas between the floor, ceiling, walls, and doors should be filled in.

Remove any debris from the area around your property.

Use broken window and door screens after repairing them.

Any entrances to the outside, the basement, the attic, and the remainder of the home should be sealed off.

Allow animals to sleep inside, especially at night

Maintain cleanliness and routinely check for pests in your home and any outdoor spaces where your pet spends time.

If you come across a kissing bug, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advise against killing it.

Better options include carefully putting the bug in a container with rubbing alcohol or freezing it in water.

The insect should then be taken to a university lab or a health organization for identification while still in its container.

The idea that these insects live inside our walls is unsettling; it reminds you of childhood tales about “monsters in the walls.”

We hope the WHO fulfills its commitment to eradicating Chagas and other neglected tropical diseases.