Despite having a brain that is exceptionally small for his size, the man manages to lead a completely normal life. His ailment was brought on by a fluid buildup in his skull.

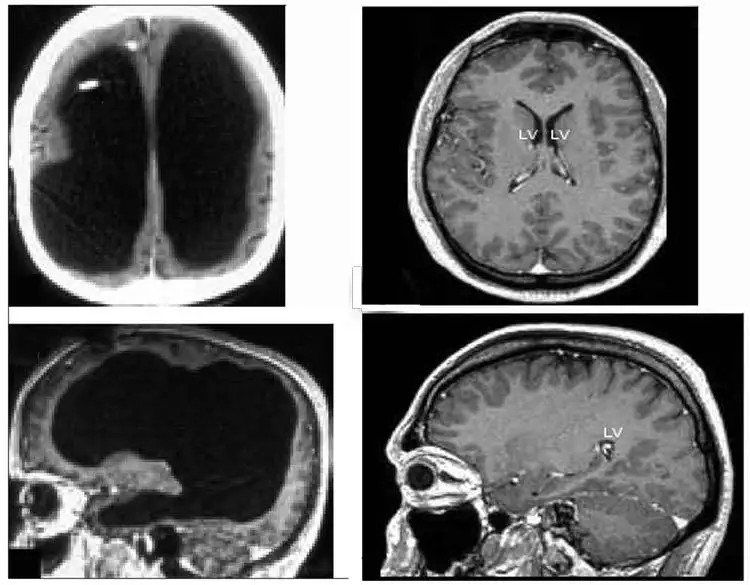

A large fluid-filled chamber in the brain called a ventricle took up most of the space in the 44-year-old man’s skull, leaving only a thin strip of brain tissue (see image of the patient’s brain, upper left).

“Since we didn’t utilize software to quantify the brain’s volume, it is difficult for me to tell with precision what percentage of the brain has been reduced.

According to Lionel Feuillet, a neurologist at the Mediterranean University in Marseille, France, “but optically, it is more than a 50–75% reduction.”

The story of this patient is discussed by Feuillet and his coworkers in The Lancet. He is a married father of two and a government employee.

After experiencing slight weakness in his left leg, the man visited a hospital. His medical history was taken by Feuillet’s staff, who discovered that as a baby, he had a shunt placed in his head to relieve hydrocephalus, or water on the brain.

When he was fourteen, the shunt was removed. However, the researchers chose to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scanning to examine the health of his brain (MRI). The lateral ventricles, which are typically tiny chambers that hold the cerebrospinal fluid that cushions the brain, were “massively enlarged,” which astounded them.

The man’s IQ was 75, which is below the average of 100 but is not regarded as mentally retarded or impaired.

“On both the left and right sides, the entire brain was decreased, including the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes. According to Feuillet, these areas regulate emotional and cognitive processes as well as language, vision, hearing, and motion.

According to him, the research shows that, with the right care, “the brain is quite malleable and may adapt to certain brain damage occurring in the pre- and postnatal period.”

Max Muenke, a paediatric brain defect specialist at the National Human Genome Research Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, US, says, “What I find surprising to this day is how the brain can deal with something which you think should not be compatible with life.”

According to Muenke, who was not involved in the case, “if something happens very slowly over quite a long time, perhaps over decades, the other areas of the brain take up functions that would typically be done by the part that is pushed to the side.”